“When you let people draw stuff on the Internet,” she told the audience, “you can be sure that they’re going to draw willies. So I built a willy detector.”

It was 2018, and I was sitting in the audience at Web Directions Summit in Sydney, watching the incredible Charlie Gerard (Senior Front End Developer at Netlifly, as at the time of writing) give a talk about how she used machine learning to detect when people were drawing penises, to stop them from submitting such drawings on a collaboration app she was working on.

To this day, I’m still not sure what amazes me more: the fact that she rapidly built a machine learning prototype that removed the need for human moderation on the Internet…or the fact that such a prototype was needed in the first place.

Why am I telling you this? Because, as we’ll see with Clubhouse, moderation is becoming a challenge for modern tech platforms - both large and small.

In this newsletter, I’ll also be touching on some product psychology concepts that Clubhouse has used to attract a global audience and build incredible levels of hype, including variable rewards, anticipatory rewards, and the scarcity principle.

PS. You can find Charlie’s talk here.

What’s the deal with Clubhouse?

If you’re active on the tech scene, you’ve probably heard of the hottest new app, Clubhouse. With a recent valuation of around US$1 billion (despite only having launched in April 2020 and being in beta mode), it’s all the tech industry is abuzz about.

So what is it?

Clubhouse is essentially an audio-only social media app that feels like an interactive podcast. You can pop in and out of “rooms” (except private rooms, which are - naturally - private) that are usually focused on a particular topic or theme (e.g. female entrepreneurs, Sydney startups, etc). The rooms are run by volunteer moderators who have the power to make other moderators, as well as bring audience members onto the “stage” where they can speak. If speaking isn’t your thing, you can just listen to the chat.

The appeal of the app is supposed to be that you can drop in on authentic, often unpolished, discussions around topics that interest you - it’s sometimes intimate, and the casual format feels like you’re meeting people at a house party. With two million users, including high-profile celebrities like John Mayer, Oprah Winfrey, Ashton Kutcher, and Drake, and well-known industry heavy-weights like Naval, Ryan Hoover, Gary Vee, and Marc Andreessen, Clubhouse is flying high.

Alright. How do I join?

One of the key drivers of Clubhouse’s current success is their exclusive, invite-only approach to its users. Clubhouse has limited the number of people on the platform by making it so that you can only join if (1) you have an iPhone (an Android version will be released at a later date), and (2) someone invites you…and boy, are invites hard to come by.

When you are invited by someone, you are usually given one invite to hand out yourself - but more interaction on the app (like moderating rooms) will reward you with more invites to hand out (cleverly encouraging us to spend more time on the app). This seems to be variable - most people report only having one invitation when they first sign up but for some reason, I got two. Further, the number of additional invites you get for engaging seem to be quite random.

This is a solid tactic. In his 1950s research, psychologist B.F. Skinner discovered the power of variable rewards. He rewarded lab mice that pressed a lever by giving them food, and found that varying the rewards (i.e. sometimes giving food and sometimes not) actually resulted in even more compulsive lever-pressing behaviour. This behaviour continued even after the rewards stopped coming. In other words, rewards are more powerful when they were unpredictable.

After realising I had randomly been awarded an extra three invites (I don’t know if it was one room in particular that led to this, or because I was given stage time in another room, or because I have been in a number of rooms), I found myself wanting to spend more time on the app, trying different things, to see if I could get more invites. (Even knowing the variable reward principle in theory didn’t stop me from this behaviour! 😅)

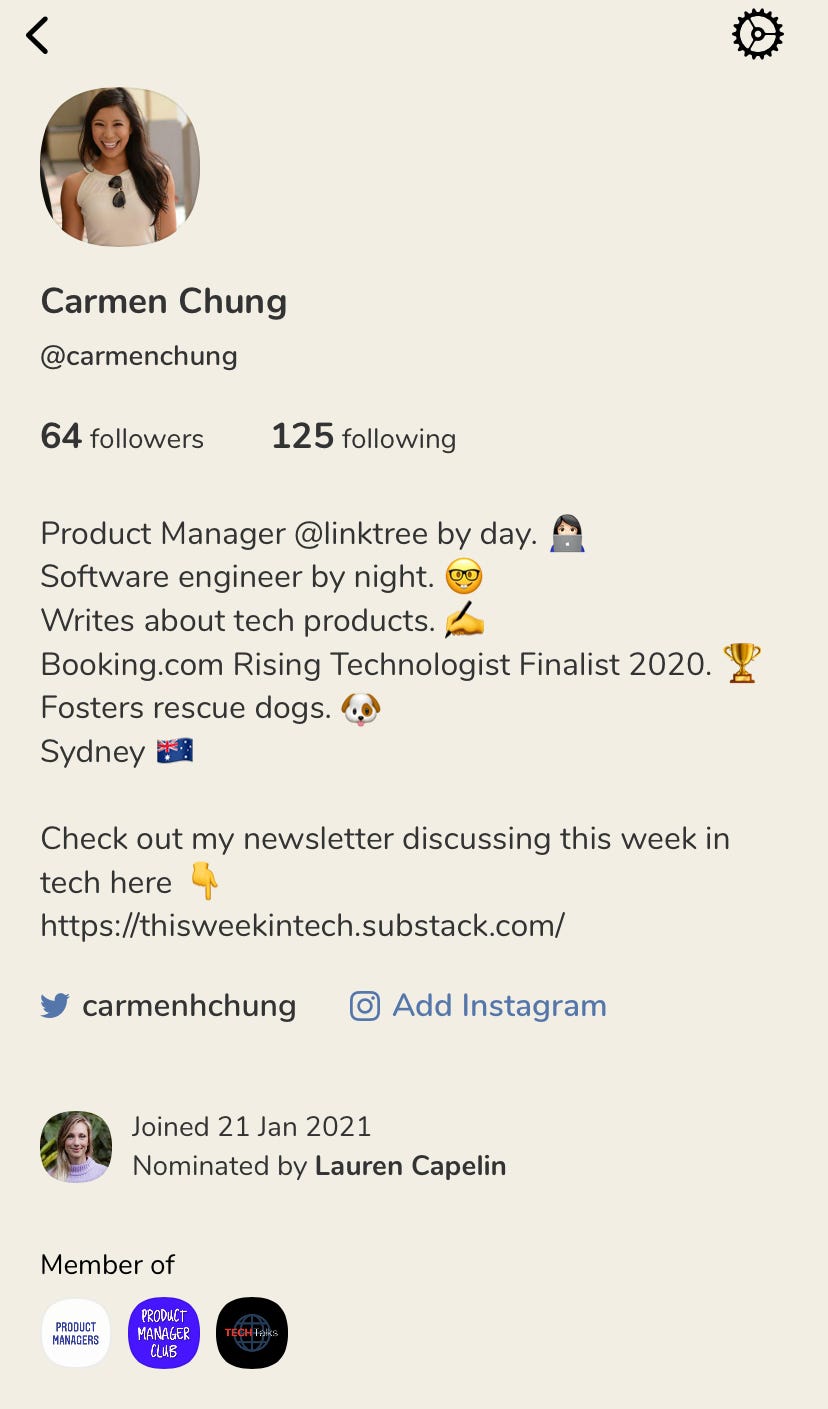

I posted a post on a product management Facebook group asking if anyone else was on the app so that I could connect with them, and I’d estimate that 35%-40% of the responses were from people who were desperate to get an invitation. The unfortunate reality is that most people are unlikely to invite those that they don’t know, because you’re required to have the other person’s number and give out your own (not sure how many people like handing out their phone number to strangers), and also because each user’s profile clearly states who invited them (big thanks to Lauren Capelin!), so you probably want to be a bit picky about who your name is associated with.

If you can’t get your hands on an invite, Clubhouse has cleverly allowed people to reserve their usernames (on iPhones only at the moment). I’ve heard that if you reserve your username, your phone contacts who are already on Clubhouse can be notified that you’re waiting for an invite, and extend one to you that way.

Why bother doing this though? Studies have shown that it’s not necessarily a reward that makes the pleasure centres of our brains light up, but rather, the anticipation of it. By reserving your username, you are not only somewhat invested in the app already, but you are also anticipating the reward of getting on the platform, contributing to its hype. This reward anticipation activates the release of dopamine before you even get your invite.

I’m not six years old. Why do people care about being part of an exclusive club?

This is a classic example of the scarcity principle: the more difficult it is to obtain something, the more valuable it becomes. If you’ve ever seen the “Hurry! 1 room left!” warning sign on any hotel booking website, you’ll be familiar with this.

In a study by Worchel, Lee, and Adewole, volunteers were given a chocolate chip cookie to taste and rate. In some cases, the cookie was drawn from a jar with lots of cookies, while in others, from a jar with only two. For some participants, the number of cookies in the jar were increased, and for others, the number was decreased. Despite the fact that all of the cookies were the same, volunteers rated the cookie drawn from the jar containing two cookies as better than the one from the jar with 10 cookies. In fact, they went so far as to rate the cookies that had gone from many to few as more valuable than those that were few to begin with!

Clubhouse takes advantage of the scarcity principle through its exclusive, invite-only approach that has helped it create a viral sensation (kind of like Gmail back in the day - that’s probably showing how old I am!). With this comes the added benefit that a number of the users who are on the platform are genuinely enthusiastic first adopters, making meaningful contributions to the rooms and hosting lively discussions. This is incredibly important to any product that relies on creator content - if you have crappy content, users won’t stay. So by limiting numbers to those who are passionate about the concept (and presumably more willing to invest their time in creating better content), the entire platform is elevated.

But isn’t this just basically an old boys’ club?

There has been some chatter about how the app is essentially a *excuse my French* circle jerk for Silicon Valley tech bros. One person commented that Clubhouse was a place for VCs to talk about Clubhouse. Others have raised concerns about whether there’s diversity on the app.

In my experience so far, I’ve seen a number of what (on the surface) would appear to be people from marginalised / under-represented communities in the rooms, but I haven’t really seen an abundance as speakers - and fewer still as moderators. That might just be a reflection of the rooms I’ve been in (which tend to be tech focused), or maybe it is a reflection of the invite-only approach, which has a danger of creating echo chambers full of like-minded people. It’s hard not to imagine private rooms being created full of flat-earthers, conspiracy theorists, Proud Boys, and extremists, all propagating misinformation.

How do they go about moderating the rooms?

Now this is where things get interesting. We’ve already seen Facebook and Twitter making the move to suspend Donald Trump’s accounts, we’ve seen AWS kick Parler off its servers - so it seems (at least for now) that the trend in big tech is towards being more open-minded to moderating content on their platforms.

But in the case of Clubhouse, most of the rooms are run by volunteer moderators with no real “moderator training”. Each club and each room are permitted to set up their own rules, and recording and transcribing conversations in rooms without every participant’s permission is strictly against Clubhouse’s terms and conditions.

From what I’ve seen, the vast majority of the conversations are not recorded, which begs the question: how will Clubhouse moderate what’s being said?

There are a dazzling array of possibilities, all with their own problems.

The first is to rely on users reporting rooms with bad behaviour. Apparently right now, a room can be reported by users, and if enough people report it, then it will be shadow banned (i.e. does not appear in search or on the home page). The problem with this idea is that a number of people could simply report a room because they don’t agree with what is being said.

One moderator in a room I was listening to said that he had hosted a LGBTQI+ chat with celebrity Perez Hilton, which attracted a number of homophobic users who were allowed onto the stage by the moderators (who obviously had no idea of their views) and were extremely vocal and abusive. What’s to stop them reporting the room and getting it automatically shadow banned just because they don’t like it?

You could say that perhaps rooms that have been reported could be reviewed by moderators - but this obviously doesn’t work when the audio is unrecorded. Furthermore, some rooms are private, and it goes against the sanctity of such rooms to have their audio reviewed. Even if you were to record the audio, some of these rooms go on for hours (I’ve literally sat in on a few that have gone on for 6+ hours), so having someone trawl through the recording would likely be a costly and time-consuming exercise.

Perhaps you could have a transcription logged at the end of the chat? The problem with this is that audio isn’t just about the words that are said - it’s also about tone (sarcasm being an obvious case in point) and even something as innocuous as a snide cough could reflect ill intentions - but this nuance won’t be captured on a transcript.

And then, of course, there’s the question of whether recording should be done by the platform at all. The drawcard of Clubhouse is that you can have a casual, unedited conversation; something that isn’t recorded and uploaded to the Internet for posterity to hear and retrospectively judge you on. Perhaps a solution here would be that only Clubhouse employees (sidenote: they are hiring for their Trust & Safety team) should be allowed to listen to the recordings.

But this is likely to trigger people’s sensitivities towards privacy issues. As I reported in last week’s newsletter, WhatsApp’s change of T&Cs caused an online furore about user privacy rights, not to mention caused a significant increase in the number of downloads of its competitors. The mere mention that Clubhouse will record audio conversations for review may be enough to undo all the hype they’re building.

Maybe one day we’ll have an audio-based AI willy detector that’s good enough to handle moderation. Until then, it’s going to be an interesting ride.

x Carmen (@carmenhchung)

PS. I ended up changing the newsletter name to This Week in Tech. As much as I loved Fix My Printer and the story behind it (which is here), I figured it didn’t make SEO sense. Plus, some people were expecting hardware tutorials. Sorry to those folks! 😂

My recommendations this week

For those who want to understand why they can’t convince Nonna that Donald Trump was a bad President: Why Facts Don’t Change Minds by James Clear. In the words of Leo Tolstoy, “The most difficult subjects can be explained to the most slow-witted man if he has not formed any idea of them already; but the simplest thing cannot be made clear to the most intelligent man if he is firmly persuaded that he knows already, without a shadow of doubt, what is laid before him.”

For those who have too many newsletters in their inbox: The T-Shaped Information Diet by Nick deWilde on how you should be intentional when curating your information diet. After all, “Our attention spans are finite, which raises the opportunity cost for subscribing to any given source. The challenge is to weed out sub-optimal information streams to make room for those that consistently deliver valuable insight.”

For those who love some of the product psychology concepts in today’s article: The book Hooked by Nir Eyal.

For those who love irony:

Have a friend ask you what Clubhouse is? Send them this post! 👇

The internet is changing a lot I loved the article and here in Brazil we made a social network focused on exactly the same subject but our market is a niche social network, and we only have an MVP launch site in April 2020, where users enter in contact with other users via voice. But the great inspiration of most registered leads want a mobile app is this is a great idea that I must apply in our app that we should launch the beta version in July 2021.